Service: +86-13485189165

The aluminum market is, to coin that phrase, a game of two halves.

On the one side we have the primary producers struggling with low prices and being kept marginally profitable by the high physical premiums paid by consumers in a highly distorted market.

However, on the other side, we have downstream semi-finished mills enjoying if not good conditions, at least growth and opportunities from uptake of new technologies by manufacturing companies and consumers.

Just look at Alcoa’s (AA) Q1 results; even with flat sales revenues, the company is making good profits. Although Alcoa is touted as the world’s largest aluminum company – a position it arguably lost to Rusal some years back – much of its income is from value-add downstream production.

Business Insider quoted Klaus Kleinfeld, Alcoa’s chairman and chief executive officer, in saying, “Our mid- and downstream businesses now account for 72 percent of our total after-tax operating income,” where the company continues to see growth even in areas like automotive, which globally is going through a lean time with sales down in Europe and India, and slowing in North America and China.

Even so, the primary end of the market still maintains a drag on many aluminum companies as the world produces more aluminum than it consumes. Alcoa sees the market in balance, but only if you count uptake by the financial community as consumption.

A Reuters article states that analysts estimate cutbacks in aluminum production have totaled as much as 700,000 tons in China, the world’s biggest consumer and producer, but at the same time is estimated to be adding up to 4 million tons of new lower-cost capacity this year.

Attempts by firms like Rusal to talk the market up by announcing cutbacks of 300,000 tons this year are having no effect, partly because the quantities are dwarfed by new capacity in China and the Middle East; and partly because while Rusal is closing old, less efficient capacity, it is refurbishing and boosting newer, more efficient capacity farther east.

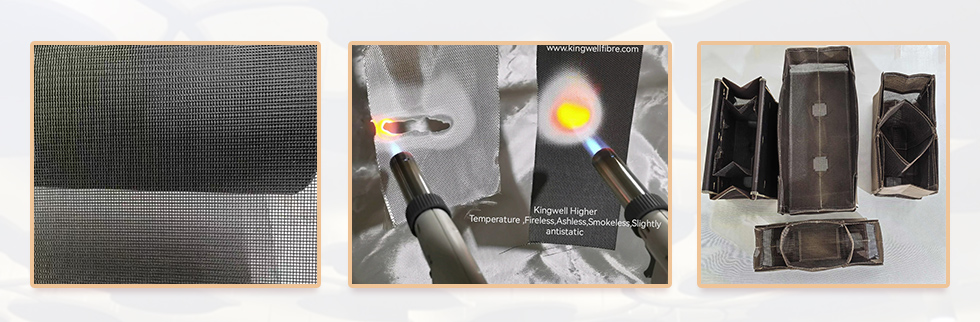

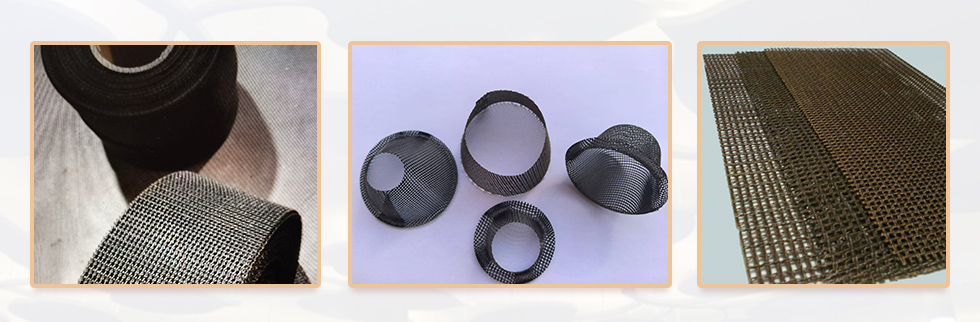

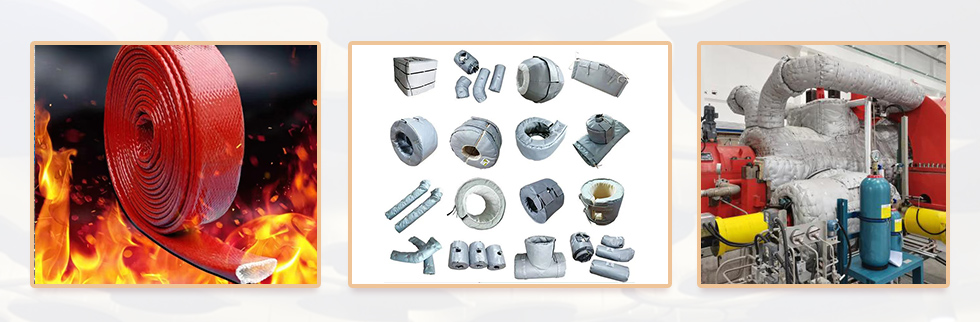

Main Products :Combo bag,Filtration,Filter,Fire Blanket, Fiberglass,Basalt,Silica,Ceramic,Carbon,PTFE,Graphite,Aerogel,Insulation

Main Products :Combo bag,Filtration,Filter,Fire Blanket, Fiberglass,Basalt,Silica,Ceramic,Carbon,PTFE,Graphite,Aerogel,Insulation